Most people get concerned about margin debt when it’s shooting up. To Doug Ramsey, the problem now is that it’s falling too fast.

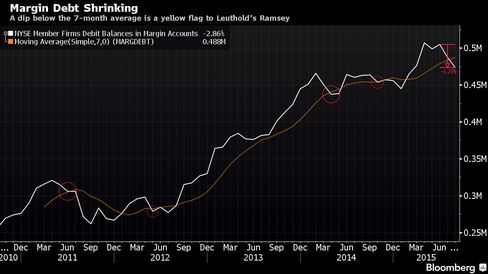

The chief investment officer of Leuthold Weeden Capital Management LLC, whose pessimistic predictions came true in August’s selloff, says the tally of New York Stock Exchange brokerage loans flashed a bearish sign when it slid more than 6 percent in July and August. The retreat took margin debt below a seven-month moving average that suggests demand for stocks is dropping at a rate that should give investors pause.

For years, bull market skeptics have warned that surging equity credit portended disaster for U.S. shares, pointing to a threefold runup between the market low in March 2009 and the middle of this year. Ramsey, who says that surge was never strong enough to form the basis of a bear case, is now worried about how fast it’s unwinding.

“Margin debt contracting is a sign of loss of investor confidence and it’s confirmation of a lot of other evidence we have that we’ve entered a cyclical bear market,” Ramsey said in a phone interview. “We got a lot of traditional warning signs leading up to the high in terms of market action, and deteriorating breadth and margin debt is important to the supply-demand analysis.”

Margin debt, compiled monthly by the NYSE, represents credit extended by brokerages for clients to buy stock. It hews closely to benchmark indexes such as the S&P 500, primarily because equity is used to back the loans and as its value rises, so does the capacity to lend.

“There’s a natural progression of the two moving together,” Tim Ghriskey, chief investment officer who helps oversee $1.5 billion at Solaris Asset Management, said by phone. “We look at it as being predictive if it gets too extreme on either side.”

NYSE margin debt surged from $182 billion to $505 billion in the six years ended in June 2015, roughly tracing the trajectory of the S&P 500, which tripled over the period. The biggest gains came in 2013, with credit rising 35 percent as U.S. stocks climbed 30 percent for the best returns in 16 years.

Since June, it’s been the other way around, with margin debt falling 6.3 percent to $473 billion at the NYSE’s last update, which covered August. The S&P 500 slid 4.4 percent at the end of that period as stocks entered a correction. To Ramsey, a decline as precipitous as that is more worrisome than the preceding run-up.

“A lot of people intimated when we broke out to a new high in margin debt a couple years ago that it was out of control, but the percentage change in margin debt from the low of 2009 was almost identical to the S&P’s,” Ramsey said. “Now that trend has rolled over.”

Owning the S&P 500 when margin debt is above its seven-month moving average returned 10.9 percent on an annualized basis since 1960, according to Ramsey’s analysis. That compares with a 7.7 percent yearly return when owning stocks while margin debt is below the average.

“As the market goes up people are willing to extend themselves and on the way down people become risk averse, so you do expect the two would move in the same direction,” said Karyn Cavanaugh, a senior market strategist at Voya Investment Management, which oversees $205 billion. “Margin debt is probably reflective of this, as a market where you’re not going to step out onto a ledge if you don’t know the support is there.”

I wonder how the algorithmic computers that do most of the trading these days will handle forced selling, unlike the 1930’s when you phoned your broker and watched the ticker tape. A skydiver in free fall comes to mind.